Calling convention

A calling convention is the way a function in a program calls another function. The compiler handles this automatically, but, if a function is written in assembler language, you must know where and how its parameters can be found, how to return to the program location from where it was called, and how to return the resulting value.

It is also important to know which registers an assembler-level routine must preserve. If the program preserves too many registers, the program might be inefficient. If it preserves too few registers, the result would be an incorrect program.

This section describes the calling convention used by the compiler. These items are examined:

At the end of the section, some examples are shown to describe the calling convention in practice.

The calling convention used by the compiler adheres to the Procedure Call Standard for the Arm architecture, AAPCS, a part of AEABI, see AEABI compliance. AAPCS is not fully described here. For example, the use of floating-point coprocessor registers when using the VFP calling convention is not covered.

Function declarations

In C, a function must be declared in order for the compiler to know how to call it. A declaration could look as follows:

int MyFunction(int first, char * second);This means that the function takes two parameters: an integer and a pointer to a character. The function returns a value, an integer.

In the general case, this is the only knowledge that the compiler has about a function. Therefore, it must be able to deduce the calling convention from this information.

Using C linkage in C++ source code

In C++, a function can have either C or C++ linkage. To call assembler routines from C++, it is easiest if you make the C++ function have C linkage.

This is an example of a declaration of a function with C linkage:

extern "C"

{

int F(int);

}It is often practical to share header files between C and C++. This is an example of a declaration that declares a function with C linkage in both C and C++:

#ifdef __cplusplus

extern "C"

{

#endif

int F(int);

#ifdef __cplusplus

}

#endifPreserved versus scratch registers

The general Arm CPU registers are divided into three separate sets, which are described in this section.

Scratch registers

Any function is permitted to destroy the contents of a scratch register. If a function needs the register value after a call to another function, it must store it during the call, for example, on the stack.

In 32-bit mode, any of the registers R0 to R3, and R12, can be used as a scratch register by the function. In 64-bit mode, the registers that can be used as scratch registers are the registers X0 to X15.

Note

In 32-bit mode, R12, and in 64-bit mode, X16 and X17, are also scratch registers when calling between assembler functions because of automatically inserted instructions for veneers.

Preserved registers

Preserved registers are preserved across function calls (scratch registers are not). The called function can use the register for other purposes, but must save the value before using the register and restore it at the exit of the function.

In 32-bit mode, the registers R4 through to R11 are preserved registers. They are preserved by the called function. In 64-bit mode, the registers X18 to X30 are preserved registers.

Special registers in 32-bit mode

For these 32-bit mode registers, you must consider these prerequisites:

The stack pointer register,

R13/SP, must at all times point to or below the last element on the stack. In the eventuality of an interrupt, everything below the point the stack pointer points to, can be destroyed. At function entry and exit, the stack pointer must be 8-byte aligned. In the function, the stack pointer must always be word aligned. At exit,SPmust have the same value as it had at the entry.The link register,

R14/LR, holds the return address at the entrance of the function.

Special registers in 64-bit mode

For these 64-bit mode registers, you must consider certain prerequisites:

The stack pointer register,

SP, must at all times point to or below the last element on the stack. In the eventuality of an interrupt, everything below the point the stack pointer points to, can be destroyed. At function entry and exit, the stack pointer must be 16-byte aligned. In the function, the stack pointer must always be word aligned. At exit,SPmust have the same value that it had at entry.The link register,

LR/X30, holds the return address at the entrance of the function.

Function entrance

It is much more efficient to use registers than to take a detour via memory, so the calling convention is designed to use registers as much as possible. Only a limited number of registers can be used for passing parameters—when no more registers are available, the remaining parameters are passed on the stack. These exceptions to the rules apply:

Interrupt functions cannot take any parameters, except software interrupt functions that accept parameters and have return values

Software interrupt functions cannot use the stack in the same way as ordinary functions. When an

SVCinstruction is executed, the processor switches to supervisor mode where the supervisor stack is used. Arguments can therefore not be passed on the stack if your application is not running in supervisor mode previous to the interrupt.

Register parameters in 32-bit mode

The registers available in 32-bit mode for passing parameters are:

Parameters | Passed in registers |

|---|---|

Scalar and floating-point values no larger than 32 bits, and single-precision (32-bits) floating-point values | Passed using the first free register: |

| Passed in the first available register pair: |

The assignment of registers to parameters is a straightforward process. Traversing the parameters from left to right, the first parameter is assigned to the available register or registers. Should there be no more available registers, the parameter is passed on the stack in reverse order.

When functions that have parameters smaller than 32 bits are called, the values are sign or zero extended to ensure that the unused bits have consistent values. Whether the values will be sign or zero extended depends on their type—signed or unsigned.

Register parameters in 64-bit mode

The registers available in 64-bit mode for passing parameters are:

Parameters | Passed in registers |

|---|---|

Integers, pointers, small structures (up to 8 bytes) | Passed using the first free register: |

Small structures (9–16 bytes) | Passed using the first free register pair: |

Floating-point values | Passed using the first free register: |

Homogeneous structures (1–4 elements of the same floating-point or vector type) | Passed using the first free registers: |

Large structures | Pointer is passed using the first free register: |

The assignment of registers to parameters is a straightforward process. Traversing the parameters from left to right, the first parameter is assigned to the available register or registers. Should there be no more available registers, the parameter is passed on the stack in reverse order.

In 64-bit mode, only the bits that are consistent with a parameter’s size can be accessed. Therefore, the called function normally sign- or zero-extends parameters that have a size smaller than 32 bits.

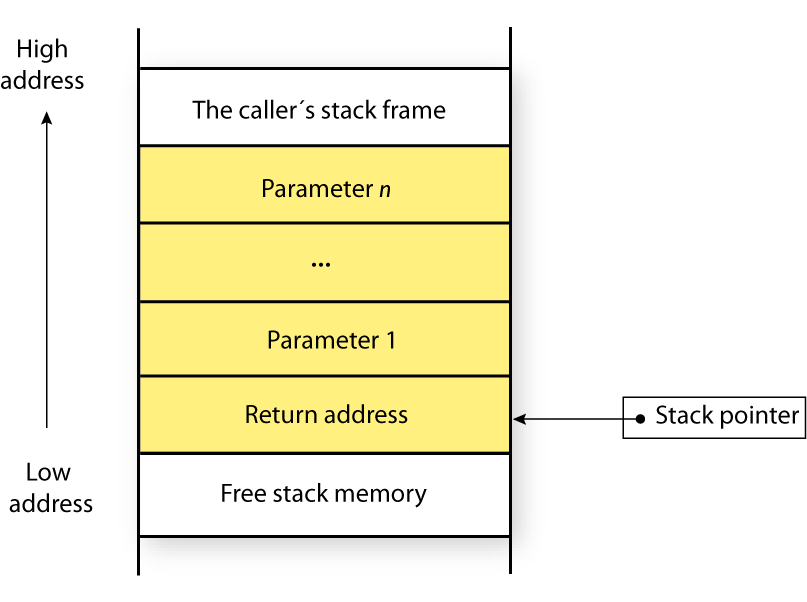

Stack parameters and layout

Stack parameters are stored in memory, starting at the location pointed to by the stack pointer. Below the stack pointer (toward low memory) there is free space that the called function can use. The first stack parameter is stored at the location pointed to by the stack pointer. The next one is stored at the next location on the stack that is divisible by four, etc. It is the responsibility of the caller to clean the stack after the called function has returned.

This figure illustrates how parameters are stored on the stack:

Function exit

A function can return a value to the function or program that called it, or it can have the return type void.

The return value of a function, if any, can be scalar (such as integers and pointers), floating-point, or a structure.

Registers used in 32-bit mode for returning values

The registers available in 32-bit mode for returning values are R0 and R0:R1.

Return values | Passed in registers |

|---|---|

Scalar and structure return values no larger than 32 bits, and single-precision (32-bit) floating-point return values |

|

The memory address of a structure return value larger than 32 bits |

|

|

|

If the returned value is smaller than 32 bits, the value is sign or zero-extended to 32 bits.

Registers used in 64-bit mode for returning values

Return values | Passed in registers |

|---|---|

Integers, pointers, small structures (up to 8 bytes) |

|

Small structures (9–16 bytes) |

|

Floating-point values |

|

Homogeneous structures (1–4 elements of the same floating-point or vector type) |

|

Large structures | Pointer is passed by caller in |

Only the bits of the return value that are consistent with the size of the return value can be accessed.

Stack layout at function exit

It is the responsibility of the caller to clean the stack after the called function has returned.

32-bit mode—Return address handling

A function written in assembler language should, when finished, return to the caller, by jumping to the address pointed to by the register LR.

At function entry, non-scratch registers and the LR register can be pushed with one instruction. At function exit, all these registers can be popped with one instruction. The return address can be popped directly to PC.

The following example shows what this can look like:

name call

section .text:CODE

extern func

push {r4-r6,lr} ; Preserve stack alignment 8

bl func

; Do something here.

pop {r4-r6,pc} ; return

end64-bit mode—Return address handling

A function written in assembler language should, when finished, return to the caller, by jumping to the address pointed to by the register LR.

At function entry, non-scratch registers and the LR register can be pushed on the stack. At function exit, all these registers must be restored from the stack.

The following example shows what this can look like:

name call

section .text:CODE

extern func

strp x9, lr, [sp, #16]! ; Preserve stack alignment 16

bl func

; Do something here.

ldrp x9, x7, [sp, #16]

ret

endExamples

The following section shows a series of declaration examples and the corresponding calling conventions. The complexity of the examples increases toward the end.

Example 1

Assume this function declaration:

int add1(int);

In 32-bit mode, this function takes one parameter in the register R0, and the return value is passed back to its caller in the register R0.

This assembler routine is compatible with the declaration—it will return a value that is one number higher than the value of its parameter:

name return

section .text:CODE

add r0, r0, #1

bx lr

endIn 64-bit mode, the function takes one parameter in register X0, and the return value is passed back to its caller in register X0. A corresponding assembler routine that is compatible with the declaration looks like this:

name return

section .text:CODE

add x0, x0, #1

ret

endExample 2

This example shows how structures are passed on the stack. Assume these declarations:

struct MyStruct

{

short a;

short b;

short c;

short d;

short e;

};

int MyFunction(struct MyStruct x, int y);In 32-bit mode, the values of the structure members a, b, c, and d are passed in registers R0-R3. The last structure member e and the integer parameter y are passed on the stack. The calling function must reserve eight bytes on the top of the stack and copy the contents of the two stack parameters to that location. The return value is passed back to its caller in the register R0.

In 64-bit mode, the value of x is passed in X0 and X1, and y is passed in X2. The return value is passed in X0.

Example 3

The function below will return a structure of type structMyStruct.

struct MyStruct

{

int mA[20];

};

struct MyStruct MyFunction(int x);It is the responsibility of the calling function to allocate a memory location for the return value and pass a pointer to it as a hidden first parameter. In 32-bit mode, the pointer to the location where the return value should be stored is passed in R0. The parameter x is passed in R1. In 64-bit mode, the pointer to the location where the return value should be stored is passed in X8. The parameter x is passed in X0.

Assume that the function instead was declared to return a pointer to the structure:

struct MyStruct *MyFunction(int x);

In this case, the return value is a scalar, so there is no hidden parameter. In 32-bit mode, the parameter x is passed in R0, and the return value is returned in R0. In 64-bit mode, the parameter x is passed in X0, and the return value is returned in X0.